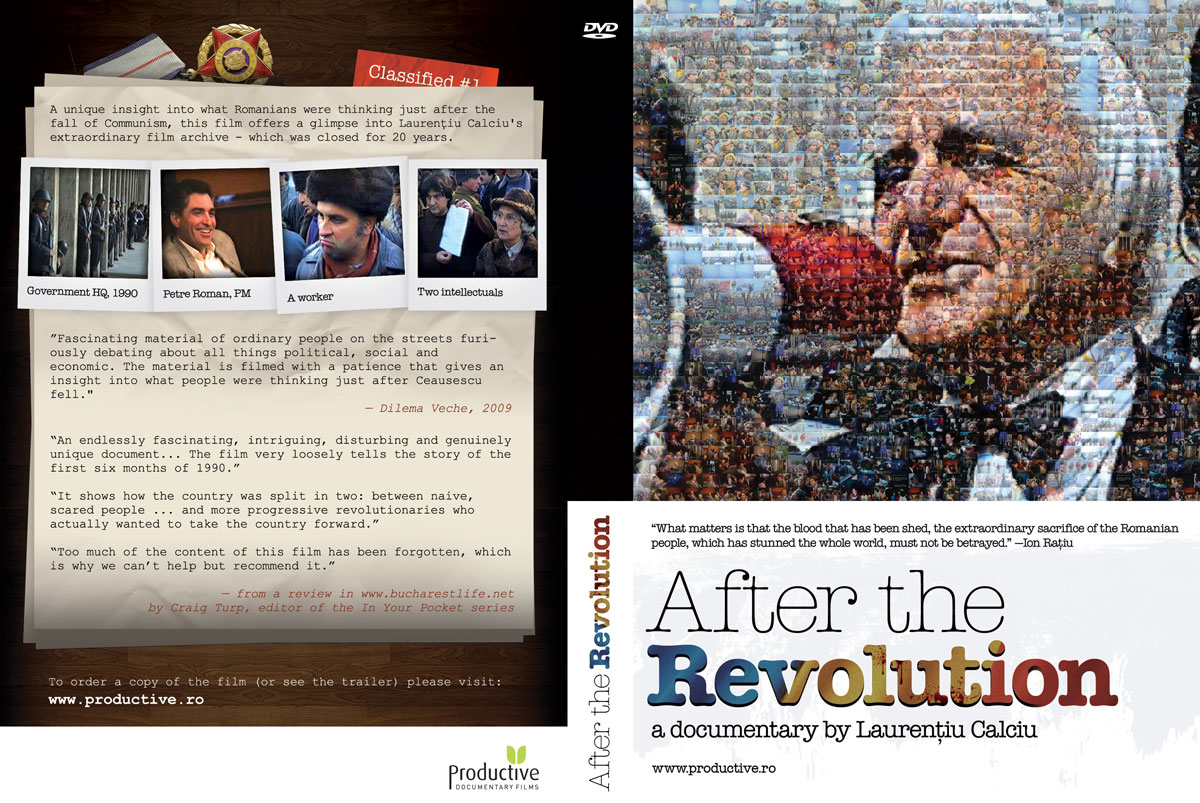

After The Revolution was recently shown at the One World Romania Documentary Festival and we’ve also made new DVDs with the film, available upon request. Below you can read and interview with Laurentiu about how it took him 20 years to make this film. And this is our cool DVD cover, by Tudor Matei.

To see the trailer on YouTube please click here

What follows is an interview with the director of this documentary (Laurentiu Calciu), first published by the Marseilles Film Festival where “”After the Revolution” was launched.

The origin of the project?

The origin of the project is as obscure as the origin of the revolution itself. I had been saving money for a video camera for about ten years, hoping to make independent films one day – fiction, as documentary would have been impossible under Communism. It was dangerous even to take photographs in the street in those days, forget about filming. I had sent the money through somebody to a friend in Berlin, in the autumn of 1989. He bought me a VHS Panasonic M7, which was the only consumer camera at that time. It arrived by post the week before the 21st of December, when the revolution had already started in Timisoara, a city in the West of Romania. I think that the Customs, which were under the control of the Securitate (secret police) at that time, have kept it deliberately, so that I wouldn’t be able to film what was happening in the streets. So I only got the camera “after the revolution”, hence the title of the film.

How did the shooting in the streets go?

It was probably the most exciting filming I ever did and the best training an observational filmmaker could get. It was the very first time I was holding a camera in my hand and some of the material in the film is actually from my very first day of shooting. What was happening in the streets was so fascinating, so tense, that I didn’t have much time to think about what I was doing. All I had to do was to press the red button, and then to press it again when I thought it wasn’t interesting anymore. Because tapes were very expensive and difficult to get hold of: with a month’s salary one could buy about three 3 hours of tapes! Also I had no idea about editing, so almost all the cuts in the main part of the film, the big street debates, were made in the camera. There was obviously no need nor was there time for asking questions or taking interviews, so that’s how I started to make direct cinema “without knowing”, before going to the National Film School in UK.

Why show this material now?

In 1990 I was too busy filming. In 1991, I went to the film school in England and then, although I knew I had some good material on those tapes, I never watched them until last summer. I kept planning to do something with them over the years: 5 years after, 10 years after, 15 years after the revolution. But I only managed to do it 20 years after!

What led you during the editing?

Initially I thought I should make a film only with the people arguing in the streets, since that was probably the strongest material I had. Then, at the suggestion of my friend and producer, Rupert Wolfe Murray – with whom I spent most of those days in 1990, when he came to Romania as a Scottish journalist, we started to add something before that sequence, then something after it and so on. The film grew from the core towards both ends. The film follows the election campaign, but you also you give a large part to the people. The central scene with the people in the street was over one hour in the first cut. Although I was never bored by watching them again and again, I felt that I should think at the audience too, if there will be any, so I started to cut it down. It was very difficult, since most of the cuts were done in the camera, most of the shots were there with a reason and with the right length, so it was almost impossible to cut them shorter or to cut them out. So all I could do was to extract whole scenes and characters from that sequence. And that was very painful, since, although I hated some of the things that people were saying, by watching them so many times I became fond of those human beings. I started to love them, they became like my family. When I watch the film, I still see some of the scenes and characters that I have cut out. They follow me like ghosts.

Another version has been screened in Romania. What’s the difference compared to this new version?

The story with the Iasi International Film Festival is the following: While I was working on the film, the producer, Rupert Wolfe Murray got in contact by chance with one of the organizers. When he found out what we were working on, he said that they have a section called “20 years after”, with films about the fall of Communism in Eastern Europe, and that they would be happy to screen our film too, if it was ready by then. Since I had only started editing in late August, early September, I gave them a 90 min rough cut that I was working on at that time, hoping to get some useful feedback for the editing process. There was no tradition in documentary filmmaking under Communism – even less of observational documentary, since it was dangerous to even take still pictures on the street in those days – so that even today the public doesn’t seem to appreciate this kind of film, with the exception of the young generation, especially some of the students. Since there was so much fuss about the revolution over the last 20 years, questioning whether it was a revolution or a coup, who organized what, who shot the people etc., Romanian people seem to be fed up with this subject. I had more request to see the film and a lot of positive feedback from foreigners, especially British people with some connection to Romania, than from Romanian people. Also, since the political and economical situation in Romania today is merely a consequence of what can be seen in my film, I’m afraid Romanian people wouldn’t be very happy to recognize themselves in the characters on the streets from those days.

Interviewed by Nicolas Feodoroff

First published in the catalogue of the International Documentary Festival of Marseilles, July 2010. Plus this short introduction to the film, on the website:

A compact crowd, faces, exchanged words, cheering. We are at the beginning of the 1990s in the streets of Bucharest, when the bloody events that marked the end of Ceaucescu’s regime are still present in people’s minds. Ion Ratiu, back from his exile in London, confronts Ion Iliescu, an apparatchik, in the presidential elections. Laurentiu Calciu, then a math professor, armed with a video camera, followed these events, always exceptional when one regime topples over, deliberately choosing to capture this hesitant word in going to meet a people who have taken to the street, observing, garnering in the tradition of direct cinema. But twenty years have gone by and the stakes have changed. News images that have become archive images, two periods interact, that of the events and that of the film. Here we are both privileged witnesses and historians. What is filming History if it is not a revolution in its movement and what gives flesh to it? What do these images say to us today? What could be the film of an election campaign reproduced in its chronology and its factual stakes, images often valuable, and a genre that includes influential works, opens nonetheless onto something else. By the length of the sequences, another approach of the image can appear, which favors the attention given to these anonymous faces, with their wordy long-takes and their body movements, their way of speaking, their dress, adding to the recited arguments a generally overlooked matter. Gaze also on an emerging utopia in a remarkable period, that of the constitution of a possible community, stretched between the epic breath of the new and the resignation during this fully politically moment.

Nicolas Féodoroff

If I were to describe this documentary in a few words, I’d say “silent power”. I believe it is a powerful film – and its power doesn’t reside in words or any sort of spoken narrative, but in the force of its images and in the way they succeed one another.

As a Romanian, I am struck by the force of the sheer scenes, caught spontaneously in various moments to create a “tableau” that is very poignant, since they bring back the memories of the tormented days of the December ’89 events. The author doesn’t make any effort to “make a point”; there is nothing “directed” in any way, as the story unfolds by itself naturally, telling the story of a changing leadership and ruling system of a country and the twisted situations surrounding it.

“După Revolutie” is an outstanding film which I would recommend to both Romanians and non-Romanians alike who wish to get a glimpse at this country’s recent history.

Mihaela

Thanks a lot for this very kind comment Mihaela. Actually it is a review and a very interesting one from our point of view as you’ve identified our filming technique very well — i.e. let the subjects make their point without us interfering; which is something that many filmmakers and TV producers try and do, but are unable to do so because of the various pressures they come under (i.e. the TV editors say “Make is sexy…make it controversial…make it confrontational…make a point” and if you don’t comply you don’t get the money. In our case we didn’t need the money as we already had the footage and we made it in our own time. It was a “zero budget” film.